Boreal

With Friends Like These

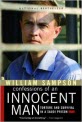

William Sampson's Homecoming

There is a technique that is second nature

to every competent diplomat when faced with having to discredit an opponent without being perceived to be doing so. It’s

a variation of the left-handed compliment, a compliment with two meanings, one of which is unflattering to

the recipient. If you do it right, your target will be completely confused as to whether he (or she) should thank you or tell you to go to hell.

There is a technique that is second nature

to every competent diplomat when faced with having to discredit an opponent without being perceived to be doing so. It’s

a variation of the left-handed compliment, a compliment with two meanings, one of which is unflattering to

the recipient. If you do it right, your target will be completely confused as to whether he (or she) should thank you or tell you to go to hell.

Done properly, it will also confuse any spectators to this exchange. They too will be unsure as to whether it was a compliment or an insult.

For those who viewed the apparent compliment as a slur, if the recipient says thank you, he or she will be perceived as naïve or in some equally negative term; for those who viewed the compliment as genuine, if the recipient responds aggressively, he or she will be viewed as ungracious or again, in some equally negative term.

Either way, if the defamer in disguise is accomplished in giving out left-handed compliments, he or she will be successful in tarnishing the reputation of the recipient for a hoped-for fifty percent of the audience; as a side-benefit, raising his or her own profile with members of the audience who appreciate the wordplay.

It was obvious that Foreign Affair’s mouthpiece on the Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs, Aileen Carroll, the then Parliamentary Secretary to the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bill Graham, had not mastered the left-handed compliment when Sampson, the man detained in a Saudi torture chamber for two and half years awaiting beheading, appeared before the Committee. Her sometimes incoherent defence of Foreign Affairs, and equally awkward attacks on Mr. Sampson only served to make her, and the Department, appear mean and vindictive.

Her less than edifying performance was only exceeded by that of her Liberal colleague, John Harvard, whose vicious attack on an innocent man who had recently faced a gruesome death, elicited, what you seldom hear in a committee room, gasps from the audience.

It was also revealed that Foreign Affairs, perhaps to soften up Mr. Sampson for Ms. Carroll and Mr. Harvard, had, before his appearance before the Committee, informed him that they were withdrawing their promise to cover his medical bills for a heart condition and other ailments he had developed during his incarceration.

Sampson and his father, who also appeared before the Committee, seem to have a personal grudge against Consular Affairs in general, and the then directory general of Consular Affairs, Gar Pardy, in particular. Why?

Consular Affairs is the section within Foreign Affairs which is tasked with helping Canadians who find themselves in difficulties abroad, usually legal ones, but also mundane inconveniences such as not having enough money to return home or losing your passport.

Father and son took Consular Affairs to task for assuming that a Canadian citizen imprisoned in a Saudi jail facing beheading was guilty, and thereby providing only lackadaisical support and making only perfunctory efforts to have him released.

Carroll would claim that this wasn’t true. Speaking for the Department, she adamantly denied Sampson's claim that consular officials assumed that he was guilty.

I am dismayed to hear your very negative judgment. My sense, indeed, was that your father was cared for in a very open way, in a way that was attempting to provide support. I would say that Mr. Gar Pardy and others did not work, Mr. Sampson, on a presumption of guilt, and I would assure you that the Department of Foreign Affairs works always on a presumption of innocence, as does the Government of Canada.

In rebuttal, Sampson recounted conversations he had with consular officials where he was told they believed he was guilty and what they told his father.

I hate to contradict you, but I'm going to.

Point one. Your embassy officials stated on numerous occasions while I was in Saudi Arabia, while I was in prison, that I was guilty.

If you were operating on the presumption of my innocence, why was it that members of your embassy in Riyadh were contradicting that? They contradicted that to my father when he was there, and they made it known to me that they considered, I think one of the quotes was, "As you are guilty...". That was a statement made to me by one of your officials. Another such statement made by one of your officials was "Considering what you have done, you must cooperate fully with the authorities."

Since I have come out of prison, I have found out the statements that had been made by your officials to my family, which completely and utterly contradict your claims that you and your department were at all supportive of my family during my incarceration.

The fact of the matter is that one of your operatives in the embassy put forward a statement to my father indicating my guilt ...

To therefore say that your department was wholeheartedly supportive of me throughout this is quite frankly nonsense. You may well have been, once you realized the full seriousness of this, but by that stage I had been in prison for a year, and by that stage I was already sentenced to death.

During that period of time, members who were being dealt with by the British embassy were certainly receiving every indication from their embassy representatives that their government considered them to be innocent, whilst at the same time I am being told by my own representative at the embassy that I am guilty.

What about the man in charge of Consular Affairs, Gar Pardy? Did he assumed William Sampson was guilty?

In a interview with the CBC, after Sampson's appearance before the Committee, Pardy was asked if Sampson was correct when he said his officials believed he was guilty. Pardy's answer is revealing — even though he doesn’t appear, in true diplomatic fashion, to support either Sampson's or Carroll's position — it has the ring of authenticity.

Pardy, assuming the mantra of someone who knows better, presented reality from Foreign Affairs point of view; a reality which, when you look beyond the diplomatic hair-splitting, you come face-to-face with that reality from Sampson’s perspective and it's not pretty.

From the prisoner awaiting decapitation's point of view, Foreign Affairs was siding with the Saudi government. From Pardy's response, he was correct to think so.

Pardy said that Consular Affairs did not deal with questions of guilt or innocence. In effect, they did not take sides.

Imagine yourself an innocent man (or woman) in a dungeon in a foreign country where prisoners are routinely tortured, about to be put to death by having your head separated from shoulders by a guy swinging a sword, and your only hope hangs with an official from your government who doesn’t believe you're innocent.

An official who does not care enough about you to assume you are not guilty, and to tell you so; who does not care enough to even provide that small amount of comfort to a countryman condemned to a barbaric public execution in a medieval desert kingdom.

The attitude of Canadian consular officials may go a long way in explaining why knowledgeable Canadians who find themselves in trouble abroad prefer seeking help at a British, Australian even an American mission because they take sides, their side.

The attitude of Consular Affairs was no different than the attitude of the newly minted Senator, Mac Harb who, after attending a reception given by the Saudi’s in Ottawa, on the heels of Mr. Sampson’s release, claimed that Saudi Arabia was being judged too harshly.

A former Canadian ambassador to the Middle East, in a television interview, echoed the Senator's sentiments: "the Saudi security forces routinely beat confessions out of suspected criminals, that is their system of justice and we must accept that."

The words of both Senator Harb and the diplomats betrayed them. They gave the benefit of the doubt to a medieval totalitarian regime, a source of funding for Al Qaeda and other terrorist organizations, over the word of one of their own, who, until the Saudi’s accusations, had led an exemplary life as a citizen of a free society.

Bernard Payeur

William Sampson died on March 29, 2012 of an apparent heart attack. He was 52.

October 25, 2008 Updated March 30, 2012