Boreal

FAREWELL POSTINGS

Failures (Partial)

October 16, 2024

Lately I have been sharing too much with people I barely know, including snippets of my favourite video, that of my late wife’s fiftieth birthday. While pointing her out to my friendly waitress, I mentioned that one of the last things she said to me was that I was the smartest man she had ever met. What a pretentious jerk I imagined her thinking as I left Abby’s Wine Bar. There was no time to provide context, so I will try to do so here.

Three failed career choices is not a sign of a smart person, but a delusional one. The reason I survived my failures was that they did not stop her from believing in me. She knew that after she was gone, there would be no one to encourage me to persevere, and she wanted me to persevere.

My first failure was the result of ignoring the advice of Sophocles who, in Antigone, warned us: “None love the messenger who brings bad news” and informed my superiors, at the then of Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs (Global Affairs), about my discovery of a multi-million dollar fraud on the Canadian taxpayers first confirmed by our Tokyo embassy and inadvertently revealed by our numbers man in Brussels duping a visit to Ottawa.

My unearthing of this massive fraud would lead to my receiving what I refer to as the Appraisal from Hell, and being fired on a bogus charge of insubordination with a hapless former Prime Minister making it possible for them to get away with it.

THE FIFTY PERCENT SOLUTION

(Abbreviated from Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books)

The Estimates contain the details of the government’s projected expenditures by department and agency. They consist of the Main Estimates and the Supplementary Estimates. The Main Estimates contain expenditure details for the upcoming fiscal year. The government presents the Main Estimates to Parliament for review and approval usually in early March, although the timing will depend on the Budget.

From the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates web page.

It's the little things that trip you up, the unexpected little things. For the diplomats, it was a request that I build a small database and user interface to facilitate the preparation of the Estimates for Parliament that would lead to the discovery of probably the largest and longest sustained raid by public servants on the public purse in Canadian history.

The preparation of the Estimates at Foreign Affairs is slightly more complicated than in other departments because a large portion of its budget is spent in other countries' currencies. The Estimates preparation process, when I was with Foreign Affairs, began in September. One of the formalities was opening The Globe and Mail newspaper to the page where it publishes the exchange rates for the Canadian Dollar against the world's currencies. These rates became the budgeted rate of exchange—the exchange rates used to convert budgeted expenditures in a foreign currency into Canadian Dollars. This Canadian Dollar total for planned expenditures for the coming fiscal year was the amount that Parliament was asked to approve as part of the Estimates process.

It is next to impossible to predict what the Canadian Dollar will be worth from one day to the next against the American Dollar, let alone accurately predict what our dollar will be worth against most of the world's currencies eight to twenty months down the road.

What you can predict with absolute certainty is that, in some countries, the Canadian Dollar will gain in purchasing power and in others, it will lose. The idea, then, was to pass on any increase in purchasing power in countries where the Canadian currency saw gains against the local currency to posts (like missions, this refers to any Canadian embassy, high commission or consulate) in countries where the Canadian Dollar experienced a decrease in purchasing power.

For example, if Parliament had authorized the rental of affordable, comfortable housing similar to that found in Canada, in Paris for instance, as guaranteed under the Foreign Service Directives (FSD), the increased purchasing power of the Canadian Dollar against the French Franc did not mean you could now rent a fancy apartment on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées complete with two fireplaces and comfortable seating for twelve at the dining room table, as was done by the Canadian accountant stationed at the Canadian embassy. You had to return any gains in purchasing power (the budgeted cost of the item or service – the actual cost) so that Ottawa could make these new dollars, courtesy of a local currency experiencing a downward trend, available to less fortunate posts where the local currency was on the rise.

If you did not return this windfall, then posts experiencing a decrease in purchasing power would be forced to draw dollars from a special emergency reserve, and when that reserve fell below a certain threshold, Parliament would be asked for more money via the Supplementary Estimates process. This is, in effect, what was happening. Canadian taxpayers were being asked to shell out millions of additional dollars to maintain adequate funding for posts experiencing a decrease in purchasing power because diplomats and their staff indulged their penchant for luxuries instead of doing what the law required by returning all of this currency windfall to Ottawa. I did not know that at the time.

It was only about a year after I joined the team completing the building of the Post Expenditures Database as part of the project with the ungainly but descriptive name of Full Telegraphic Input of Financial Data (FTIFD) project, that I discovered what was happening.

The Auditor General, in a previous audit at Foreign Affairs, had expressed concern as to the timeliness and accuracy of the reporting of expenditures by posts. To fix this problem, Foreign Affairs had embarked on the ambitious and innovative FTIFD initiative. Expenditures made by all posts would be transmitted via the department’s worldwide communication network on a weekly basis to its powerful mainframe computer (a DEC-20 from the now defunct Digital Equipment Corporation of Maynard, Mass.) in Ottawa, then quickly sorted, analyzed and summarized and made readily accessible for review and action by management.

As an incentive, and so as not to add to the administrative burden of posts, expenditures would be reported in the currency the goods or services were paid for; the DEC-20 would convert all expenditures made in a foreign currency into Canadian Dollars based on the exchange rate that accompanied every transaction.

Full telegraphic input meant that, for the first time, the exchange rate used by posts to convert Canadian Dollars into the currency of the host country, as well as the cost of goods or services, was available in electronic format on the same computer where the Estimates Database that I had built and still managed was located. What did the Estimates Database contain? The exchange rate at which posts’ budgets had been approved by Parliament. The department and its posts were not aware of the significance of this development.

During the implementation phase of Full Telegraphic Input of Financial Data, I spent a lot of time, at all hours of the day and night, in front of a computer terminal waiting for some post halfway across the world to send in their information. Before the information was packaged to be included in the Post Expenditures Database, I quickly scanned it for obvious errors or fixed errors detected by error-detection programs before drafting a telex, i.e., telegram, telling the post that had sent the information what they had done wrong.

It was late one night, while waiting for the information from Warsaw or Ouagadougou to arrive, that I realized I could eliminate the need for posts to calculate gains and losses on foreign currency transactions altogether. All I had to do was link the Post Expenditure Database and the Estimates Database (child's play), write a program to calculate gains and losses, and build a database to store the information. The time savings would be impressive. It took more than one hundred (100) people around the world sometimes days to perform these calculations every month using pen and paper and a desktop calculator, something the DEC-20 could do in a matter of hours.

It took more than a few months, working part-time and after hours, to put together what became known as the Currency Fluctuation Reporting System. Most of the time was consumed in writing programs to produce summary, and detail reports for each Canadian embassy, high commission and consulate. Back then, there was no sophisticated off-the-shelf programs to do this. You had to program every type of report from scratch and this took time. Also, the DEC-20 could only do arithmetic to seven decimal points. This was not good enough to get an absolutely accurate calculation for countries like Italy where the Lira had plummeted to an all-time low. Situations such as this added to the programming complexity.

The actual calculation done by the computer was of course quite simple. The following formula is easily understood by anyone who has ever traveled to a foreign country and had to convert Canadian dollars into the local currency.

(Expenditure in Local Currency x Budgeted Exchange Rate) – (Expenditure in Local Currency x Local Exchange Rate) = Gain or Loss on Transaction

Finally, I had processed more than a year's worth of information and produced the first complete set of computer printouts that would become known as the Currency Fluctuation Report. It was time to show my calculation to the boss, Dave Gordon, the Director of the Financial Planning and Analysis Division. Gordon was incredulous. “That can't be,” he said. “The gains indicated are at least twice what posts are reporting.”

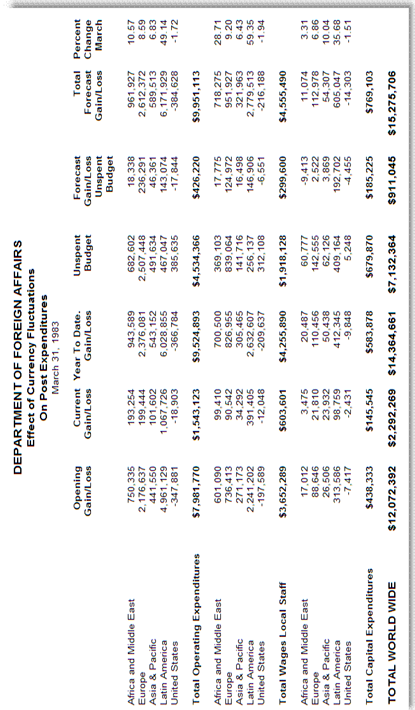

Following is a one page summary of currency gains and losses on expenditures experienced by Canadian missions around the world in the fiscal year ending March 31, 1983. The following one-page monthly summary would have been supported by at least 200 pages of detailed calculations. In the column labelled Year-To-Date Gain/Loss the report shows that the Department of Foreign Affairs has made more than 14 million dollars on foreign currency transactions. For the same period, missions abroad reported gains of approximately half that amount, and that is how the multi-million dollar fraud was discovered; a fraud that had been going on for a number of years.

Why did I wait so long? I was doing this on my own time or when there was nothing else to do. I enjoyed the challenge. I was also doing the type of complex programming that was not part of my job description. I was afraid that, if I told anyone before I was far enough advanced, I might not get to finish what I had started.

TOKYO LETS THE CAT OUT OF THE BAG

(Excerpt from Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books)

Gordon requested that I draft a telegram (telex), for his signature, asking our embassy in Tokyo to confirm that they had under-reported gains on foreign currency transactions by at least one hundred thousand dollars. Tokyo had been chosen as a test to confirm the accuracy of my calculations because of its reputation for impeccable bookkeeping. Tokyo's initial response was not at all what Gordon and I expected.

Tokyo dispensed with any diplomatic niceties in its telegram telling Gordon what he could do with his calculations. Dave Gordon was a proud and ambitious man. Not only had I made him look like a fool but, if Tokyo was right, a potential windfall of more than seven million dollars had just evaporated, a tidy chunk of change even then. Further savings could be expected as lengthy, tedious calculations previously performed by support staff around the world were now done by a computer in Ottawa.

It was not only more than seven million dollars for the 1982 fiscal year that was gone but promises of even greater savings down the road. This was not a trivial thing for the man ultimately responsible for the preparation of the Estimates to Parliament. The head of the Estimates and Budgets Section, Hugh Burrill, reported to Gordon. It was for Burrill’s section that I built the Estimates Database.

Gordon was not a happy man when he showed up with Tokyo's response. I was working at one of the computer terminals in a restricted access room (then, access to all computers was tightly controlled; even personal computers were kept in this room) when he showed up. He only came close enough to where I was sitting so that when he flew Tokyo's telegram like a Frisbee in my direction, it landed on my desk. "Answer this," he said, and walked out.

I wasted no time in getting the powerful DEC20 to print out every financial transaction of the Tokyo embassy and the rates of exchange (both the budgeted and actual rates) used in the calculation of what they owed in currency gains. I pitied the next courier headed for the Far East. It had only taken Tokyo a few days to respond to my (Gordon's) first telegram. Going over the massive computer printout delivered by diplomatic courier took a bit more time, measured in weeks.

I was busy, as usual, at a computer terminal when the director showed up with Tokyo's second telegram. He did not look happy, but this time he did not throw it at me; this time, he handed it to me. The telegram contained an apology. Tokyo wrote that after a detailed review, my numbers were correct; so, why the gloomy disposition? This was a time for celebration or at least congratulations.

Looking back, I am convinced that Tokyo was aware all along that my calculations were correct. This would explain the embassy's over-the-top reaction to the first telegram. The tone of their initial response was probably their way of telling Gordon, in no uncertain terms, to back off. When they realized that proof existed in Ottawa as to what posts had been doing (for a number of years, it would later be ascertained), it was time to adopt a different strategy, a strategy that would have to involve Ottawa.

There was no thank you or apology from Gordon; just a request for a printout of the gains and losses for all posts by geographical area (Africa and Middle East, Europe, Asia Pacific, Latin America, and the United States). He wanted the printouts for his next meeting with the so-called Area Comptrollers scheduled for later that morning.

What is an Area Comptroller? Foreign Service Officers, as part of what is called re-Canadianization (getting re-acquainted with Canadian values after so much time spent in countries that don’t share them), are rotated back to Ottawa after two or more postings. Area Comptrollers were usually Foreign Service Officers in Ottawa on a re-Canadianization tour. Each was assigned a geographical region and given overall administrative responsibility for managing budgets and tracking expenditures for their respective region. In retrospect, there was really no point in producing the more than 300-page currency fluctuation printout. So why did Gordon sacrifice a few trees? Was he still unsure about what to do next?

The Currency Fluctuation Reporting System had not only identified additional savings of more than seven million dollars but also an apparent fraud on the taxpayer and Parliament that had been going on for years. The cat was out of the bag. Evidence of what had been going on was in the computer printouts that Tokyo acknowledged as accurate.

When I showed up at the director's office with the information he requested, Gordon asked if I wouldn't mind meeting with the Comptrollers. They were waiting for me in the division's small boardroom. This was highly unusual. I had never dealt with them directly. In fact, to the best of my recollection, I had never met any of them. Furthermore, a middle grade Financial Officer was, in effect, being asked to negotiate the return of more than seven million dollars, probably fraudulently obtained, with five experienced diplomats. I was, of course, not being asked to do any such thing.

With the massive computer printouts under my arm, I made my way to the boardroom where the Comptrollers were said to be waiting. They were all seated on one side of a medium-sized round table. They did not get up. I don't remember them introducing themselves. We definitely did not shake hands. What I remember is placing the printouts, which I had separated by geographical region, in front of them and having them gently pushed back. What I also remember is that they were not the least bit interested in talking about dollars and cents.

"We already know what your report contains," said the Comptroller directly across from me, the one who did all the talking. It soon became clear why I was the only one invited. It was not a meeting to discuss the return of ill-gotten gains. I had been invited to a lecture. The Comptrollers' unexpected tribute to the hardworking diplomats did not last more than five minutes. To the best of my recollection, here is the essence of what the guy in front of me had to say:

Foreign Service officers are doing an important job under difficult circumstances and deserve to be compensated for their hard work and dedication, something the government is not always willing to do. Under the circumstances, the Foreign Service was justified in keeping a portion of the gains made on foreign currency transactions.

At the end of this homage to the poor, unappreciated, hardworking Canadian Foreign Service officers, I was told to take my reports with me and get out. Until I met with the Area Comptrollers, I was convinced that under-reporting of currency gains was a simple mistake. Now I realized it wasn’t. I briefed my director about my meeting with the Area Comptrollers. Gordon told me to continue producing the Currency Fluctuation Report on a monthly basis and give them to him. He would look after them. I did so for more than two years. I respected the chain of command and trusted him to do what needed to be done.

*****

The Comptrollers’ justification for diplomats and their support staff helping themselves to moneys to which they were not entitled implied that what they did was not really a crime. The people pocketing those extra benefits had secure jobs, above average salaries—way above average when you factored in the perks that come with being a member of the Foreign Service serving abroad—and after what they claimed was onerous work on behalf of ungrateful taxpayers was done, a generous pension, largely funded by those same ungrateful tightwads, awaited them.

A MUGGING IN AMSTERDAM

(Excerpt from Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books)

The multi-million dollar fraud on the Canadian taxpayers and Parliament could not have been carried out without the assistance of the department’s financial officers and bookkeepers. Foreign Affairs had scores of these on its payroll. Financial Officers were stationed on a permanent and semi-permanent basis in London, Paris, Brussels, Tokyo and Washington. Smaller posts had at least one locally engaged staff (LES) to look after the books under the supervision of Foreign Service personnel or non-rotational Canadian staff on temporary assignment abroad.

It was purely by accident that I discovered that our accountant in Brussels, along with the one in Paris with the luxurious apartment described earlier, were in on the fraud. I ran into our man in Brussels coming out of Gordon’s office during a short visit to Ottawa. I could not resist asking him how it was possible for Brussels to have under-reported gains on foreign currency transactions by at least a quarter of a million dollars. .

He was not as eloquent as the spokesman for the Area Comptrollers in explaining his role in the theft of tens of millions of dollars. Glancing around, he whispered: “Listen, it’s always been the practice; we always only reported half the currency gains. Ottawa was happy and we kept the rest.”

Unlike the Canadian Financial Officer stationed in Paris who was there on a multi-year posting, our numbers man in Brussels was non-rotational, returning to Ottawa every four months. It was on one of these return trips to Ottawa that he was mugged by a man holding an ice cream cone. It happened while he was transiting through Amsterdam. He and the man with the cone both tried to get into the same cab at the same time, with the inevitable result that our much-travelled accountant ended up wearing the man’s ice cream.

The man apologized profusely and tried his best to clean up the mess he had made, and in the process, also removed our bookkeeper's passport and wallet which contained four thousand dollars (a hefty chunk of change even now). I was a little surprised when he submitted a claim for the stolen cash, and it was paid. The legal term is an “ex gratia payment”, meaning there was no legal obligation to give him the money.

I don't doubt that the money was stolen, but what was he doing coming back to Canada, after a four-month stay in Belgium at the Queen’s expense, with so much paper currency in his wallet?

THE APPRAISAL FROM HELL

(Abbreviated from Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books)

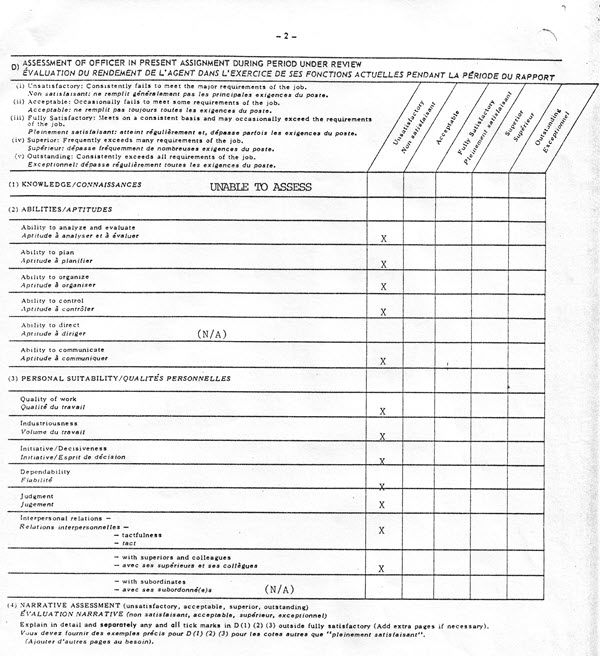

Days had stretched into weeks and weeks into months as I sat alone in my little grey cell wondering when the axe would fall, when Richard invited me into his office. My scheduled annual appraisal was at least four months away when he presented me with a very special performance review on which Gordon had already signed off. What I refer to as The Appraisal from Hell rated me a complete moron unable to accomplish the simplest of task, incapable of making informed decisions, undependable and incoherent.

In my twelve years as a public servant, I had never received an appraisal that had rated me less than fully satisfactory, if not higher. This hateful appraisal was nothing less than character assassination. Director General Dan Bresnahan—the leader of, for lack of a more appropriate label, what I refer to as the character assassins—had told Chrétien, during the ambassador's investigation into my allegations, that a Special Appraisal—with which both his Directors, Gordon and Dunseath, had agreed—was being prepared that would rate me "unsatisfactory on all rating factors." The ambassador was obviously okay with that, his affirmations about my character during our previous meeting notwithstanding.

I sat across from Richard reading what the character assassins had to say about me. Richard was not smiling; he was serious. He did not say a word, letting the implication of what they intended to do sink in.

Richard: "Are you going to sign it?"

"No."

Richard: "It will go on your file anyway, and you know what that means."

If it went on my file, I would effectively become unemployable in both the public and private sectors. That appraisal would be available to any prospective employer. Such an appraisal was also grounds for immediate dismissal or, at the very least, a trip to the psychiatrist. They had decided the less risky route for my dismissal was insubordination; they had no intention of using The Appraisal from Hell to seek my dismissal on grounds of incompetence or mental defect. We both knew that my dismissal, which was imminent, was going to end up before the courts, something they wanted to avoid.

Richard: "Look, you agree to leave and I tear it up. We forget the whole thing. What will it be?"

What Richard, Gordon and company saw as an incentive to leave, I saw as incentive to stand my ground. If that appraisal went on file, it would be proof positive in any court proceeding of Foreign Affairs' deceitful, duplicitous conduct, or so I thought. I did not sign it. The Personnel Bureau gave its blessing anyway; the report went in my personnel file and I was given a copy.

For a government official to destroy an employee’s reputation using this type of appraisal—Barth’s quotation notwithstanding—is not an easy task. That is, unless the assassins can count on the acquiescence of those whose responsibility it is to stop these bloodless, surreptitious murders. At Foreign Affairs, that collective responsibility was shouldered by R. G. Woolham, Director General of the Personnel Administration Bureau. The personnel administration I knew when I was a manager would never have signed off on such an obvious travesty; either the employee had completely lost his mind or his bosses had gone mad. This gave me hope.

The Appraisal from Hell was unassailable proof of the gangster mentality at Foreign Affairs. All I had to do was hang in there until my objections to this despicable assessment of a man's character and abilities reached a level where competent and ethical people in positions of authority could be found.

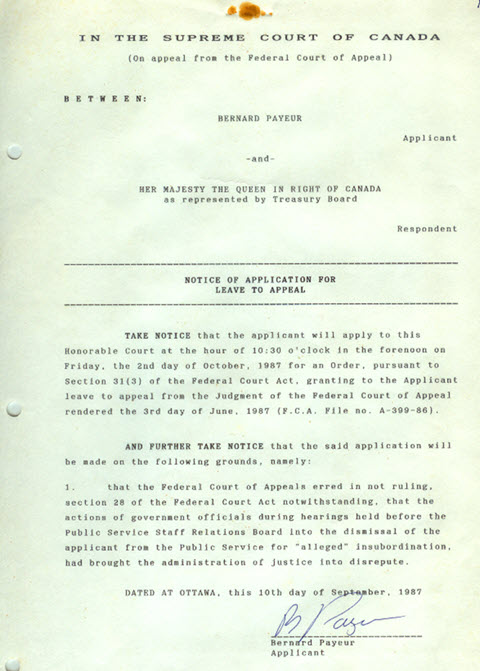

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA

(Abbreviated from Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books)

The Right Honourable Chief Justice Brian Dickson

The Honourable Mr. Justice William McIntyre

The Honourable Mr. Justice Antonio Lamer

Robert Cousineau, Q.C., counsel for HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA and Treasury Board.

John E. McCormick, Esq., counsel for the Public Service Staff Relations Board

Bernard Payeur representing himself

Image may be subject to copyright

I had just stepped up to the lectern and was getting ready to address the Court when a group of school children on a field trip were ushered in by their teacher. If anything, they would learn a valuable lesson about getting justice in Canada that day. I had fifteen minutes to convince the Supreme Court of Canada to grant me leave to appeal the judgement of the Federal Court of Appeal. Even if I had been given more time, I did not want to repeat the mistake I had made in Federal Court by telling the whole story. I again prepared my arguments after reading old Memorandums of Points of Arguments given to me by the always helpful Court staff.

*****

During the two years it took to appeal my firing all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, using leading edge Canadian software I built a computer application that I would use as my calling card to find work despite the Appraisal from Hell.

It was not quite ready when my appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was dismissed, not on its merit, but because, in the words of The Right Honourable Chief Justice Brian Dickson, it was “not a question of national interest.”

A few days after The Right Honourable Chief Justice Brian Dickson said those discouraging words and invited me to leave his courtroom, I received word that someone wanted to offer me a job.

André’s small Montréal-based computer consulting firm had won an impressive contract to provide user support to the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), and he was looking for someone to manage the young people he would be sending to Ottawa. I took the job.

Sharing a drink at a bar during one of his visits to Ottawa I told André that I had inadvertently found out who he bribed at CIDA and at the then Department of Supply and Services to obtain the contract. He was candid about it.

He knew whoever he hired to manage his operation at CIDA would eventually find out and that is why he hired me. Knowing my history, he was confident that after what they did to me for telling on my bosses I would not make that same mistake again, and he was right. And that is how corruption becomes endemic (see Chapter “CIDA,” Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books).

We parted on good terms; after all, he had saved my marriage and possibly my life when he offered me a job.

THE SHELL TO THE RESCUE

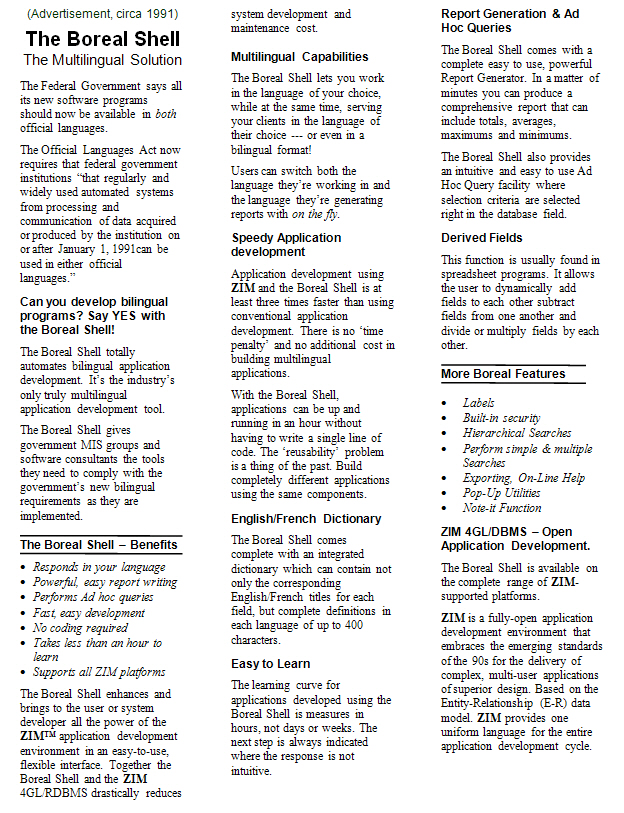

The Boreal Shell was now ready for prime time:

I started my own consulting firm, Boreal Consulting and used the shell to get clients. My first client was the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC).

Denis was a man with a big problem on his hands. He was the civil engineer in charge of a computer project to catalogue all assets for which the Federal Government was responsible in the more than 800 First Nation communities, i.e., reserves, across Canada, and that included everything from roads to fire halls and firefighting equipment, water treatment plants, schools, etc.

His first attempt at creating a database had taken more than a year and was an abject failure; the highly touted American DBMS (Database Management System), PowerBuilder, proved inadequate for the task. Indian Affairs would be the first to adopt the Boreal Shell.

Government departments are notoriously shy about trying unproven Canadian technology like the Boreal Shell, and to make matters worse, it was based on a Canadian DBMS with the unfortunate name of ZIM; a name which completely obscured the powerhouse that was the ZIM DBMS and the ZIM fourth-generation language, leading edge technology from Bell Northern Research, the precursor to Nortel.

I made Denis a promise that normally would have been considered reckless. I promised him that, using ZIM and the Boreal Shell, and starting from scratch, I could have the thing done in four months. Not only that, but it would include a user-friendly interface and a feature that no other database product on the planet offered at that time: the ability to respond to the user in the language of his or her choice, in this case English or French, and produce reports on the fly in either language. If I did not deliver what I promised within the agreed-upon timeframe, he did not have to pay me.

He was impressed enough that he gave ZIM and the Boreal Shell a chance, and he never looked back. The system, which became known as CAIS for Capital Asset Inventory System, was built within the time allowed and implemented within all the Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC) regional offices across Canada.

With the success of CAIS, I was asked to build the more complicated companion system, ACRS (Asset Condition Reporting System, pronounced acres). Every year, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs must estimate and allocate the amount of money it will need to maintain First Nations’ community assets in good working conditions and to track projects related to the maintenance of these assets. This was the role of ACRS. ACRS won the Deputy Minister's award for excellence, coming in on time, under budget, and exceeding requirements and user expectations.

The next few years were good years, then the government declared ZIM’s super-efficient way of retrieving information not compliant with an old standard developed by IBM 30 years earlier called SQL (pronounced sequel) which it adopted as a government-wide standard (see Chapter “The Butterfly Effect,” Shooting the Messenger, Boreal Books). This not only made it next impossible to get new government clients, but existing ZIM clients started abandoning the DBMS (Database Management System) in favour of inferior American products.

One of my clients, the Ontario First Nations Technical Service Corporation based in Toronto stayed with ZIM and the Boreal Shell. In doing, so with the assistance of Michael Cowpland of Corel fame who had recently acquired the ZIM Corporation they would have succeeded in saving this cutting-edge Canadian gem until the rest of the industry caught up, had it not been for the perfidy of INAC.

Around the time I was building CAIS, and later ACRS, the Government of Canada announced a policy whereby First Nation communities were going to be given the resources, training and technology to manage their communities. As part of this policy of devolution, there was to be a transfer of computer-based management information technology to the First Nations, and part of that transfer included CAIS and ACRS.

I went to work for the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation (OFNTSC) to make it happen. On its website, OFNTSC describes its mission as a “technical advisory service for 133 First Nations and 16 Tribal Councils in Ontario.”

Under the visionary leadership of Chief and Executive Director Irvin George and the project management skills of Elmer Lickers, an Iroquois from Six Nations of the Grand River, OFNTSC had the potential to become the provider of custom-made, leading edge computer applications for First Nation communities across Canada and beyond.

We merged CAIS and ACRS and added a housing database and call the new integrated system CAMS for Community Asset Management System. Housing on reserves is the responsibility of the Federal Government. As landlord to the First Nations, it had not been able to solve what seemed to be an intractable problem: getting timely information on housing conditions in Native communities, especially in the North. OFNTSC was looking to remedy that situation by adding a housing component initially called CAHD for Conditional Assessment of Housing Database.

Teams were sent out to collect what should have been destined to become a digital life-cycle record of every house in every community, including information about the sex and age of occupants and sleeping accommodations so as to identify overcrowding that might invite sexual interference. We incorporated within the housing component the complete Canadian Building Code. This allowed for quick verification when a request for payment was received for repairs done, along with a digital photo of the work done, it was done according to code.

In less than a year, thanks to the Boreal Shell as both an interface and development platform and people who knew what they were doing, we had a working application. Communities were accepting of the CAMS not only because of its ease of use but also because it was presented as a First Nation achievement, which it was (and also a Métis achievement: Dewey Smith, a Métis, was the expert in the voluminous Canadian Building Code incorporated into the system as a set of pop regulations), and they would be made custodians of the information collected about conditions in their communities.

CAHD catalogued perhaps a thousand homes—mainly in poor Northern Ontario

communities such the house pictured here—when the dream came to an end.

CAHD catalogued perhaps a thousand homes—mainly in poor Northern Ontario

communities such the house pictured here—when the dream came to an end.

OFNTSC had a vision of being a management software provider to First Nations across Canada, and to that end, Elmer and I went to B.C. to demonstrate our application to the B.C. INAC regional office.

They were more than impressed and wanted to start using CAMS immediately. Next came Alberta, to whom we sent a prototype. They all wanted it. There was only one catch: we estimated that to make CAMS available to all 800+ First Nations communities would require at least a million dollars.

The housing component was OFNTSC’s idea but its development was funded by the Federal Government. INAC said the money for the development was a contribution, as opposed to a grant, therefore, as the one and only contributor—as if sweat equity and devolution did not matter—they owned it and would now take over the CAMS.

OFNTSC refused to hand over the application and the source code that made it run. To try to convince INAC to let OFNTSC handle the deployment of CAMS, I got Michael Cowpland, who had recently purchased ZIM, to partner with OFNTSC and make a joint presentation to departments. Michael even agreed to throw in $250,000 of free ZIM software to keep our first year’s estimated deployment costs at or below a million dollars.

A small group—consisting of Irvin George, Bill Taggart, OFNTSC’s general counsel, Elmer Lickers, a Ms. Batson from ZIM Technologies, and myself—met with an assistant to Minister Nault to make our case.

Bill Taggart actually made the most compelling argument. Holding a CAMS installation CD in one hand, he waved it in front of the bemused assistant, telling him, “You have here an easy-to-use, elegant, inexpensive solution tailored to First Nations peoples’ needs; what more could you want?” An ugly request put an end to any substantial discussion about an “easy-to-use, elegant, inexpensive solution” to a pressing problem.

Another argument was that CAMS, especially in northern communities, could be the difference between life and death. The aide's response was to ask us to produce a cost benefit analysis for the Minister, which at this point should not have been necessary. In that analysis—I kid you not—he wanted us to include an estimate on how much the life of an "aboriginal" was worth.

Michael Cowpland, when he heard about this preposterous demand, correctly concluded that they were wasting our time and wanted nothing more to do with INAC. Unbeknownst to any of us at the time, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada had probably already signed a $20,000,000+ contract with Accenture, the large American software integrator, to build Internet-based CAMS with ORACLE as the DBMS. Their wanting ownership of the community-based CAMS, instead of letting a First Nations organisation proceed with its implementation across Canada was to kill it in favour of Accenture.

We asked for a million dollars for a proven system that had found favour among those it was meant to help. Accenture wanted—and got—20+ million dollars to build a system that the First Nations could never trust having their participation relegated to that of data entry clerks.

I got the opportunity to ask a consultant with Accenture about the initial 20 million dollars, an amount I found excessive, knowing the problem to be solved. “Because we don’t know what we’re doing,” was his reply. A Freudian slip, or was he simply being facetious? Considering that they never managed to duplicate the CAMS, I would opt for the former.

In the fall of 2019, I got a call from Elmer, who was in town on business. Did I have time to meet him for a game of pool? He had some news. After almost twenty years and a slew of costly failures, INAC had finally relented and was ready to adopt the community-based solution we had proposed way back when. They had given OFNTSC the money to build a new CAMS using a mainstream DBMS and language, ZIM having withered on the vine.

In all those intervening years, Elmer had kept a working copy on an out-of-the-way computer. When he met with the developers to show them what he wanted, he simply fired up the old machine and gave them a demonstration of our CAMS. He said they were absolutely blown away. They could not believe that what he was showing them was twenty years old. They even admitted, he said, that they could not easily duplicate some of the features even today.

He thought I would be happy to hear that. I was and I wasn’t. That is the way with what-might-have-beens.

My last client for the Boreal Shell was Bell Canada Enterprises. With the help of the smartest manager I have ever worked with, we beat Google to Google only to have new management abandon the project days before going live.

It was post 9/11, after I had returned from Montréal for good, when I picked up a copy of the Koran in the hope of understanding what happened that fateful day and decided to write about it. It is a failure in progress.