Boreal

FAREWELL POSTINGS

Prologue

I was born in Hearst, Ontario, a mostly French-speaking town about 150 miles southwest of James Bay on a northern leg of the Trans-Canada Highway. When the glaciers retreated, they deposited a lump of clay in the middle of the great Canadian Shield, and on this lump of clay, in the middle of muskeg and stunted pine trees, grew the town of Hearst.

On this lump of clay, hardy farmers managed to grow some vegetables and enough forage to support some animal husbandry—mostly dairy cattle—but it is with the logging industry that Hearst is first and foremost associated.

Sawmills were the town’s primary economic growth engine. Whenever a new sawmill opened in or near the town, Hearst experienced a mini economic boom. Those who could profit from these periodic booms, by risking big and not going bust, would be set for life. Enough did that it was said that Hearst had, at one point in time, more millionaires per capita than any other town in Ontario.

Many of the people who got rich were those who obtained the contracts to supply these sawmills with trees and, to a lesser extent, the vendors who sold and maintained the equipment to harvest the forest for these sawmills. My father was one of these vendors.

I was not yet a teenager when Hearst experienced another of these economic booms. This time it was not just another sawmill that was coming to town, but a plywood plant. A plywood plant whose appetite for trees would dwarf the demand of most of the sawmills that doted the Hearst landscape. The owners of the logging companies, who would get the contracts to supply what some claimed was destined to become the largest plywood plant in the world, would be the new millionaires.

My father teamed up with one of the owners of a small logging operation. His company financed the purchase of the equipment the logger would need to make him a serious contender for these lucrative contracts. The logger did not get the sought-after contracts and my father was left with having to pay for a large assortment of expensive logging equipment, only a portion of which could be resold to the successful bidders. My parents might have been able to weather this setback if fate had not been particularly unkind and if my father had not used this setback as an excuse to drink more heavily than usual.

It was sometime in June after midnight when I was awoken by people shouting and the glow from a fire that illuminated the basement bedroom where I slept. The house next door was on fire. The family home, along with most of its contents, was quickly reduced to a pile of smoldering embers when the fire next door caused a rupture in the natural gas line where it entered our house. This momentarily turned the gas line into an impressive flame thrower that spewed fire into every corner of the basement where three of my siblings and I, only a short time earlier, had been sound asleep.

My parents loved this nondescript little town floating on a lump of mud in the middle of a swamp. Hearst was home. They were middle-aged and the idea of being left homeless and penniless with six children still at home must have been frightening. They rebuilt the family home after the fire, but not enough time had passed to build any equity when their worst fear became reality. In the fall of 1967, Traders Finance forced them into bankruptcy.

On a cold Sunday afternoon in November, in a scene reminiscent of The Grapes of Wrath—with a snowstorm threatening, my mother at the wheel, and my father nursing a bottle of gin or rye—the family set out on a journey of more than 2,000 miles to begin again. A few hours into the journey, the gently falling snow became a blizzard. Somehow we made it to Thunder Bay where we spent the night...

[Seven years later] I am not sure why I chose to come to Ottawa. It may have been the glimpse I got of the city from the train I took to Expo 67. I knew I had missed something. In high school in British Columbia, because I came from (Northern) Ontario, whenever Ottawa was brought up, they assumed I knew the city and what went on there. I didn’t, but I was curious about what it would be like to work for the Federal Government, even for a short time.

I made the return trip in early September when I was half my mother’s age and conditions were ideal. She did it in near-winter weather during the unpredictable month of November. She drove more than two thousand miles in under three days, driving from sunrise to past sundown on a highway where four lanes were the exception; driving from dawn to dusk with four kids in the back seat, the youngest in the front sandwiched between her and an alcoholic husband who could not be trusted to help with the driving.

As I encountered one familiar sight after another from that remarkable journey, I could not help but marvel at the courage it took. Three days after leaving Kelowna, I was in Ottawa having a cold beer on the terrace of the National Arts Centre next to the legendary Rideau Canal. Now, where to stay?

A few months after arriving in Ottawa, I took the public service exam and was invited to join the federal government. Twelve years later, I was terminated for alleged insubordination after discovering a multi-million dollar fraud at the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs (today Global Affairs).

During the two years it took for the appeal of my dismissal to be heard by the Federal Court of Appeal then the Supreme Court of Canada—the Right Honourable Chief Justice Brian Dickson dismissed my last hope with a curt "not a question of national interest”—I developed a ground-breaking software application I christened The Boreal Shell.

The Boreal Shell was, for a number of years, our salvation. It opened the door to consulting contracts in both the public, e.g., Indian Affairs and private sector, e.g. Bell Canada Enterprises based in Montréal.

It was shortly after 9/11 when, spurred on by the events of that day, and what a young African immigrant I met in Montréal told me about her religion, that I bought an approved translation of the Koran and quickly read it from cover to cover. It more than lived up to Edward Gibbon’s assessment of “as toilsome a reading as I ever undertook; a wearisome confused jumble.”

I was both a programmer and a systems analyst; the latter skill often involves bringing order to chaos. Could I do the same for the Koran and make it more accessible to the layperson and perhaps making a living as a writer? The result was Pain, Pleasure and Prejudice: The Koran by Topic, Explained in a Way We Can All Understand.

EULOGY

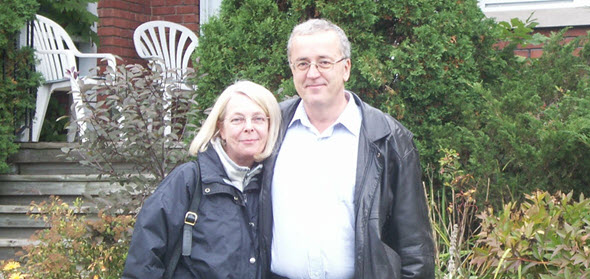

Lucette Carpentier BA, MA, MBA

September 1947 - July 2019

I used to be a different man. Today, I would like to think I am a better man,

and I had nothing to do with it. It is all her doing, and I told her so on our

wedding day. I told her almost forty years ago that I was marrying her not only

because of the person she was, but the person I became when I was with her, a

person I liked.

I used to be a different man. Today, I would like to think I am a better man,

and I had nothing to do with it. It is all her doing, and I told her so on our

wedding day. I told her almost forty years ago that I was marrying her not only

because of the person she was, but the person I became when I was with her, a

person I liked.

I asked her to marry me a year into our relationship. She said no - something about my not being ready. Four years later, thinking I was ready, I asked her again. She said yes.

I was still not ready.

About a month into the wedding preparations, she sensed uneasiness. She asked if I wanted to go through with it. I was no longer sure. Without the slightest hesitation, and without the slightest hint of recrimination, she cancelled the whole thing.

We did not talk about getting married again until a few years later.

We had now been seeing each other for about seven years. We were playing backgammon at my place. I think I was winning when she said, “if I win this game, we get married.” She liked to talk about how she won me in a game of backgammon. I like to think I let her win because I would have been a fool not to.

I met my future partner in life in 1973 at Communications Canada. She was a professional translator on a temporary assignment at the agency. Four years earlier, she had moved to Ottawa from Montreal, her hometown, to complete, on a scholarship no less, a Masters of Linguistics at Ottawa U.

Lucette was the only child of Adélard Carpentier and Anne Marie Mercier. They came from Montreal to join her in a large apartment on Elgin Street. I spent, maybe seven years of wonderful Sunday evenings with her and her kind and generous parents. Evenings which began with a lovely supper and ended with a game of cards or watching Les Beau Dimanche.

I would not have had the courage to ask that beautiful young woman in an enclosed office still working away on a Friday afternoon, but it was either giving it a try or admitting to my sister Rosa, who was in town with her husband Laurent for a teachers conference, that I did not have a date for a ball at the Chateau Laurier, to which they had invited me.

Lucette loved to dance. She admitted later that that was the reason she accepted my invitation. She would get to dance. I definitely did not woo her with my awkward impression of Fred Astaire. But still, at the end of the evening she said she would like to see me again. Thank you, Lord.

For our second date, I invited her to my studio apartment where I cooked for her what I thought was a simple dish. Most of our conversion that evening ended up being a back and forth with me alone on the bed and her in the bathroom getting over my impersonation of someone who knew how to cook. She decided then and there that, from now on, she would be doing the cooking. That was a bonus. I was just glad she still wanted to see me.

Shortly after we became an item, she joined the elite of government translators/interpreters: the fifty or so professionals who provide translations services and simultaneous interpretation to the House of Commons, the Senate of Canada, Parliamentary and Cabinet Committees and Party Caucuses.

Her range of interest, her knowledge of art, food, history, her extensive travels, before and after we met, meant that many an evening, when she could not talk about her day because of that secrecy thing, there was always still plenty to talk about.

Later, during the years when I was working in Montreal, she completed a Master of Business Administration, adding economics and commerce to our conversations. I loved talking economics, having taken a few courses at Simon Fraser during my phase I think I want to be an economist, only to be stumped by the mathematics. This was not the case for Lucette; she loved numbers. Soon she was doing my tax returns and doing them much better than I could.

Having a dilettante for a husband, a husband who was never sure if he was doing what he was meant to do, did not faze her one bit. She took it all in stride. Because she believed in me, I started believing in myself.

Before joining the Public Service Lucette taught French as a second language at Ottawa U. One summer the University sent her to Aix en Provence, all expenses paid, to teach French to adult Canadians looking for the ultimate immersion experience.

Lucette made friends easily. It was inevitable that her students became more than acquaintances. When the Public Sector told me to take a walk, she contacted a former student who paved the way to a successful career for me in the private sector as a consultant in computer-based information systems.

Lucette once joined me and new business partner on a trip to London to meet with clients who had expressed an interest in an application I had developed. On landing, Gerry and I ignored her advice ˗ a bad idea ˗ that we all get a good night's sleep, and headed off to the Soho bar and theater district where we promptly got mugged.

Again, she took it all in stride, just a slight admonishment that we were businessmen on a mission and not tourists, and we should behave that way. The next evening, she got us three of the best seats to an amazing production of Les Miserable at the Palace Theater. When the cab driver asked her, “where to?” she said: “The Palace.”

"Buckingham Palace ma’am?” he enquired. An understandable mistake.

With Lucette’s providing corporate guidance and home-cooked meals we did well.

My last years as a computer consultant would be spent at Bell Canada headquarters in Montreal. As I mentioned earlier, Lucette used the opportunity to earn an MBA while tending to her day job and her responsibilities as Vice President of her Union. Where she found the time and energy to meet me at the train station every Friday and drive us home to a table set for two and a romantic dinner, I will never know.

Lucette was 34; I was 30 when we married. She told me she could not wait forever to have children. I was never ready and forever came to pass. She was a great partner and I am sure she would have been a great parent and an even greater grandparent.

As an only child she will have to depend on the memories of other than her progeny to recall the wonderful, resourceful, and thoughtful person that she was. That is where I come in.

You may have noticed, as you entered, a book about a book which some of you may think out of place. Her DNA may not live on, but the words we crafted together and the message they convey will, of that I am sure.

It was shortly after 9/11 when I walked into my local Chapters and noticed a pile of Korans stacked near the entrance. I purchased one, took it home and started reading. I had always dreamt of writing something more useful than a User’s Guide for a Management Information System.

I told Lucette that I would like to write about what I had read and would re-read many times over. I expected it would take me a year or two, three at the most to complete a sort of layman’s guide to the Koran. Ten years was more like it. Ten years that turned out to be some of the best years of our time together.

Most days began with the buzz of the alarm clock; my signal to get up and go downstairs to make the coffee. Ten minutes later, a warm cup of coffee in each hand, I would make my way back up the stairs, leaving one cup on the desk in my home office, and the other on her bathroom vanity.

Back in the bedroom I would open the curtains, then walk over to the bed to kiss her good morning. She would shower and get dressed and I would drive her to her job on Parliament Hill—a five to ten minute drive depending on the traffic.

After a hurried goodbye and a "have a nice day"—Wellington Street, in front of Parliament, is a busy street in the morning—I would make my way back home and begin my day’s work, bringing order to the Koran.

When she got home at the end of the day, depending on the season, and the weather, we would sit on the front porch with a glass of wine and some munchies and she would read and comment on what I had accomplished that day. I always had a copy of Fakhry’s interpretation of the Koran on my lap ready to answer her questions. This was when her Masters in Linguistics - Specialty Translation came in handy.

Sipping her wine, she would patiently explain some of the nuances of Fakhry’s translation that I had failed to grasp or that I might have misunderstood.

We agreed on most things when it came to Islam and the threat it posed to Western Civilization except, that she believed it would all come to pass, that the moderates would win the day and the March of Civilization would continue and we would not see the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, which ushered in the Age of Reason, undone.

She was always the optimist. As our layman's guide to the Koran grew from a few hundred pages to encompassing the entire book, her optimism was severely tested, but her dedication to what would become our project to make the Koran accessible to the layperson never wavered.

If we can, believers and non-believers, have the type of discussions Lucette and I had about Islam then her optimism that a modern interpretation of the Koran and mutual respect and understanding will eventually overcome fanaticism and intolerance may be validated and nothing would make her happier.

Love you Lucette

Bernard

July 11, 2019

A BELATED ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

In this cowering new age where an honest appraisal of a religions text or of the man who revealed its content to mankind is a death defying act, I thought it prudent not to acknowledge her contribution while she was alive. Lucette passed away on the afternoon of July 5, 2019.