Boreal

SHOOTING THE MESSENGER

The Appraisal From Hell

![]() McGahey had tried to rid the department of my person by attempting to provoke

a physical confrontation. Others took a less risky route, that of character

assassination. If the threat of character assassination did not convince me to

leave quietly, they would still have the satisfaction of having destroyed my

reputation, which, like most people, I valued most. As Allan Barth wrote:

“Character assassination is at once easier and surer than physical assault; and

it involves far less risk for the assassin. It leaves him free to commit the

same deed over and over again, and may, indeed, win him the honours of a hero.”

McGahey had tried to rid the department of my person by attempting to provoke

a physical confrontation. Others took a less risky route, that of character

assassination. If the threat of character assassination did not convince me to

leave quietly, they would still have the satisfaction of having destroyed my

reputation, which, like most people, I valued most. As Allan Barth wrote:

“Character assassination is at once easier and surer than physical assault; and

it involves far less risk for the assassin. It leaves him free to commit the

same deed over and over again, and may, indeed, win him the honours of a hero.”

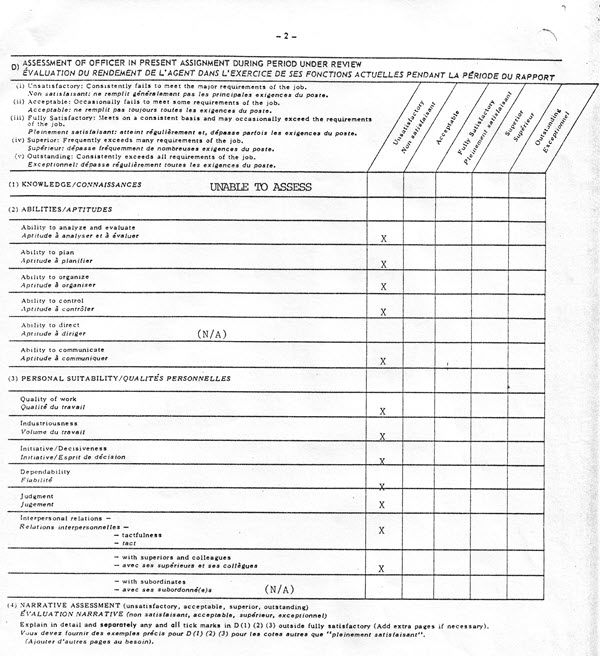

Days had stretched into weeks and weeks into months as I sat alone in my little grey cell wondering when the axe would fall, when Richard invited me into his office. This was after my meeting with McGahey. My scheduled annual appraisal was at least four months away when he presented me with a very special performance review on which Gordon had already signed off. What I refer to as The Appraisal from Hell rated me a complete moron unable to accomplish the simplest of task, incapable of making informed decisions, undependable and incoherent.

In my twelve years as a public servant, I had never received an appraisal that had rated me less than fully satisfactory, if not higher. This hateful appraisal was nothing less than character assassination. Director General Dan Bresnahan—the leader of, for lack of a more appropriate label, what I refer to as the character assassins—had told Chrétien, during the ambassador's investigation into my allegations, that a Special Appraisal—with which both his Directors, Gordon and Dunseath, had agreed—was being prepared that would rate me "unsatisfactory on all rating factors." The ambassador was obviously okay with that, his affirmations about my character during our previous meeting notwithstanding.

I sat across from Richard reading what the character assassins had to say about me. Richard was not smiling; he was serious. He did not say a word, letting the implication of what they intended to do sink in.

Richard: "Are you going to sign it?"

"No."

Richard: "It will go on your file anyway, and you know what that means."

If it went on my file, I would effectively become unemployable in both the public and private sectors. That appraisal would be available to any prospective employer. Such an appraisal was also grounds for immediate dismissal or, at the very least, a trip to the psychiatrist. They had decided the less risky route for my dismissal was insubordination; they had no intention of using The Appraisal from Hell to seek my dismissal on grounds of incompetence or mental defect. We both knew that my dismissal, which was imminent, was going to end up before the courts, something they wanted to avoid.

Richard: "Look, you agree to leave and I tear it up. We forget the whole thing. What will it be?"

What Richard, Gordon and company saw as an incentive to leave, I saw as incentive to stand my ground. If that appraisal went on file, it would be proof positive in any court proceeding of Foreign Affairs' deceitful, duplicitous conduct, or so I thought. I did not sign it. The Personnel Bureau gave its blessing anyway; the report went in my personnel file and I was given a copy.

For a government official to destroy an employee’s reputation using this type of appraisal—Barth’s quotation notwithstanding—is not an easy task. That is, unless the assassins can count on the acquiescence of those whose responsibility it is to stop these bloodless, surreptitious murders. At Foreign Affairs, that collective responsibility was shouldered by R. G. Woolham, Director General of the Personnel Administration Bureau. The personnel administration I knew when I was a manager would never have signed off on such an obvious travesty; either the employee had completely lost his mind or his bosses had gone mad. This gave me hope.

The Appraisal from Hell was unassailable proof of the gangster mentality at Foreign Affairs. All I had to do was hang in there until my objections to this despicable assessment of a man's character and abilities reached a level where competent and ethical people in positions of authority could be found. All I needed to do was hang on just a little longer. What I did not anticipate was Woolham running interference on behalf of the assassins.