Boreal

SHOOTING THE MESSENGER

From Witness to Malfeasance to that of Malevolence

![]() It was shortly after 9/11. Spurred on by the events of that day and what

a young African immigrant I met in Montréal had told me about her

religion—our time together is the subject of one of the stories in Love,

Sex & Islam—I bought an Al-Azhar approved translation of the Koran and

quickly read it from cover to cover.

It was shortly after 9/11. Spurred on by the events of that day and what

a young African immigrant I met in Montréal had told me about her

religion—our time together is the subject of one of the stories in Love,

Sex & Islam—I bought an Al-Azhar approved translation of the Koran and

quickly read it from cover to cover.

The Koran is a short book by holy book standards: an English translation of the Koran will run to about 77,700 words, the approximate size of a standard 300-page book. That first reading more than lived up to Edward Gibbon’s [1737 - 1794] assessment of “as toilsome a reading as I ever undertook; a wearisome confused jumble” and Thomas Carlyle’s [1795 – 1881] "a confused, jumble, crude, incondite (disorderly), endless iteration." Is it any wonder so few non-Muslims have read the book?

I was a both a programmer and a systems analyst; the latter skill often involves bringing order to chaos. Could I do the same for the Koran—make it accessible to the layperson— and perhaps make a living as a writer? The result was Pain, Pleasure and Prejudice: The Koran by topic, explained in a way we can all understand.

I thought it would take two years, three at the most; ten was more like it, with the expected dividend failing to materialize. During those ten years I would publish five editions, reading Islam’s core religious text from cover to cover each time. The last edition contained the entire Koran in order, together with historical context.

For reasons I can’t remember, I took a couple of courses in script writing. The instructor said I had a gift for dialogue. With that endorsement, I wrote my first script. It was a long one in which my newfound knowledge of Islamic scriptures allowed for a perspective I would not have otherwise considered.

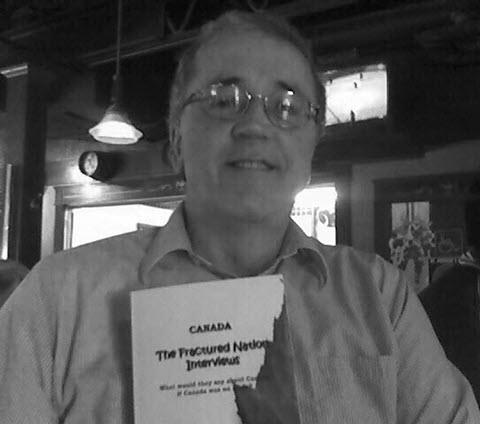

In 2005, I self-published Canada: The Fractured Nation Interviews. The Interviews would be my bestseller, even if that doesn’t mean much, in part because of a column by the Calgary Herald’s Les Brost. In a letter to Canada masquerading as a column, he wrote:

Dear Canada:

It might seem strange to write a letter to a country rather than a person, but there's a first time for everything. I'm writing because next Sunday is our 140th birthday, and I figured that it was a big enough number to deserve a birthday present…

That's why my perfect birthday present to Canada would be to help start a national discussion about the Canada we want to see for our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

I recently found a stimulant for that kind of national discussion. It is a book written by Bernard Payeur and published by Trafford Publishing in Victoria called Canada:

The Fractured Nation Interviews. It imagines a world where Canada has been broken up for almost 10 years. The book uses a series of five imaginary television interviews to trace the root causes of the breakup…

Read it only if you are prepared to think -- really think -- about tomorrow's Canada...

Let's recapture values we love, Les Brost, For the Calgary Herald, June 25, 2007.

An established Ottawa producer expressed an interest in producing a mini-series of sorts if I got rid of the interview with the Ayatollah, saying: “I don’t want to open my front door one morning and be confronted by a guy with a bomb.”

I couldn’t do that. I have since posted the entire interview with the fictitious Muhammad Abdullah on my website. The segment where the discussion strays into Khomeini’s views on sodomizing baby girls and sex with chickens (Appendix: Khomeini on Sodomy and Bestiality) is the most downloaded page on Boreal.ca by a factor of at least ten to one. One read and you may understand why the founder of Sound Venture Productions wanted it out. The Interviews were nominated for the 2006 Sunburst Award for Canadian Literature of the Fantastic.

In 2012, I published Alice Visits a Mosque to Learn about Judgment Day, a one-act, thought-provoking, often brutal (it could not be otherwise), sometimes funny play/script about an important concept in Islam on which the Koran expounds at length.

In October of 2013, thinking that time was not on my side, I stopped working on Going Swimming Fully Clothed, a comprehensive introduction to Islamic law, to concentrate on a less ambitious manuscript about what Muhammad said and did that informs the decision of Sharia tribunals to this day. In approximately four weeks, I assiduously read 6,275 of the hadiths collected by the celebrated Bukhari, and a few thousand more by lesser luminaries, about what the companions of Muhammad and his child bride Aisha remembered he said and did.

I thought Pain, Pleasure and Prejudice: The Koran by Topic, Explained in a Way We Can All Understand was the most important book you could read about Islam. After completing 1,001 Sayings and Deeds of the Prophet Muhammad, I am not so sure.

Within the house of Islam, the penalty for learning too much about the world—so as to call the tenets of the faith into question—is death.

While the Koran merely describes the punishment that awaits the apostate in the next world, the hadith is emphatic about the justice that must be meted out in this one: “Whoever changes his religion, kill him.”

Given the fact that [hadiths are] often used as the lens through which to interpret the Koran, many Muslim jurists consider [them] to be even a greater authority on the practice of Islam.

Sam Harris, The End of Faith - Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason, 2004, W. W. Norton & Company.

My next book on the Koran explored a curious and not insignificant concept, that of abrogation. The Verse of the Sword, which nullifies any pretense to compassion for those who refuse to submit to the Will of Allah, is its most momentous and violent manifestation. Of all the incongruities that devotees of a religion steeped in incongruities have to accept, the concept of abrogation has to be the most outlandish. For the rational mind it is inconceivable that a god, in a book in which He lays claim to infallibility, has to retract or modify what He said earlier. Welcome to Let Me Rephrase That!

Children and the Koran, a comprehensive argument against exposing children to the hate, violence and brazen sadism of Islam's core religious text followed.

In August 2018, my wife’s lungs had deteriorated from a cancer, and an infection diagnosed as Kansasii, to the point there was nothing more her doctors could do. With less than a year to live, we moved into a retirement home that accepted palliative case residents. Looking after her was a pleasure that allowed me time to begin work in earnest, with her as my always reliable sounding board, on a book that I had put off for more than ten years.

A friend said he had given up on Pain, Pleasure and Prejudice because of all the verses, which he felt interfered with the story. He challenged me to write the story of Islam without the interruptions. I thought it impossible. Not anymore! Remembering Uzza: If Islam Was Explained to Me in a Pub would be our last collaboration. With her wholehearted agreement, the book is dedicated to the young immigrant from West Africa who is the inspiration for Uzza.

In a posting on my website, a few months after my wife's passing, I wrote that I owed Lucette’s friends an explanation as to why, when I told her that a young African working girl was crashing at my apartment in Montréal, all she said was she would like to meet her.

My explanation took on a life of its own and that is how I found myself writing, during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, a book about love, sex and Islam. Love, Sex & Islam compares sex in the now with sex in the Hereafter in an effort to convince believers who may be contemplating martyrdom that it’s not worth it, despite what they have been told.

In my writings on the Koran, Muhammad and Islam, in the tradition of Thomas Paine, I have tried to explain the seemingly complicated in terms we can all understand in what became, after my wife's passing, a solitary campaign against the willful ignorance that will be our undoing.

I have been asked, on more than a few occasions, why I write about the Koran, and the alleged illiterate who was purported tasked by God with acquainting mankind with its content, knowing the consequence of a one wrong word, a typo or a misspelling, let alone a book-length challenge to orthodoxy. The danger is there, but it is nothing compared to the risk we ask our young people to take when we send them to fight religious extremists like the Islamic State, the Taliban, Al-Qaeda... Unlike yours truly, they jeopardize lives not yet lived in what many have to know is a forlorn battle because of what is happening at home.

With the new race and religious hate laws coming through [after the London bombings] it could be considered illegal if Pain, Pleasure and Prejudice is deemed an attack on a person’s religious belief.

A British publisher expressing his regrets.

Words, the most effective weapon against an advancing darkness, are being rationed in a futile attempt to appease an intractable foe who lives, murders and dies as per the instructions contained in an inviolate book whose provenance and error free status is vouched for by the book itself. "Epistemological black holes of this sort," writes Sam Harris, "are fast draining the light from our world."

The darkness cannot smother the light on its own. It requires our complicity, our collective willful ignorance of what is behind "the draining of the light." I will not be an accomplice, the reason for turning my attention twenty years ago, at this writing, from being a witness to malfeasance to that of malevolence.