Boreal

LOVE, SEX & ISLAM

Falling for Uzza

Part I

![]() Hers is a Koranic name, meaning it was derived from a chapter in the

Koran. Her name is about emotions, strong emotions evocative of the

passion a grieving man once felt for a cherished partner when she was

alive and well.

Hers is a Koranic name, meaning it was derived from a chapter in the

Koran. Her name is about emotions, strong emotions evocative of the

passion a grieving man once felt for a cherished partner when she was

alive and well.

She asked for assistance in dying at the beginning of July once she realized that the first full draft of Remembering Uzza was complete. I said she couldn’t leave because there was still much to do; still, I did not insist when, a few days later, she called the number that would bring the doctor who would end her suffering to our apartment.

I spent most of the sunny summer of 2019 at the bar and restaurant patios that dot both sides of the street close to where we used to live working on that draft and thinking about her, and, later, the girl with the Koranic name who, with only a few words and a smile, soothed my longing for my beloved Lucette.

It was my first visit of the year to this particular bar and patio. It would not be my last. I sat down at an out-of-the-way table some distance from the serving area when I first spotted her: a beautiful tanned vision of confidence, in what I think was an imitation of the proverbial little black dress, making her way to my table, a gentle breeze kissing her hair.

While taking my order she glanced at my draft copy of Remembering Uzza.

[Beautiful girl]: Is that a book about Islam?

Me: Yes.

[Beautiful girl]: Who is the author?

Me: That would be me. It’s not published yet. I am making corrections.

[Beautiful girl]: Oh! I am Arab and Muslim.

Me: That’s nice.

What else was I going to say? For the rest of the afternoon the service took on a decidedly matter-of-fact quality. The subtitle If Islam Was Explained to Me in a Pub may have had something to do with it. I don’t know, and I didn’t care.

A week or so later I found myself sitting in a different section when she rushed over and asked the waitress who was about to take my order if she could have this table. She was actually smiling when she inquired how my book was coming along. That is how it started, our mostly random, maybe once-a-week conversations at her workplace about Islam and about her.

I can’t tell you much except that she was twenty-something, beautiful and smart, and had the academics to prove it; I want her to remain anonymous. I was very much interested in her as a person but also as a Muslim. Nearly two decades of studying Islamic scriptures and I am still trying to understand how ostensibly rational individuals can embrace a religion steeped in incongruities, whose core theology stripped of all pretences can be summarized in three little words: worship, war and sex, the latter being mainly a man’s commensurate reward for his level of commitment to the first two.

It’s probably a generational thing, but my interest in her was only reciprocated by her interest in the book that was, in so many ways, about her and young forward-thinking Muslim female immigrants like her. It became even more so as the parallels between her and the heroine of Remembering Uzza could not be avoided. I once remarked that, if Uzza’s character had been Arab instead of Pakistani, she could be Uzza.

She made me promise I would let her read my book as soon as it was published. I said I would love for her to read it and let me know her thoughts. I even stoked her interest by revealing elements of the story with which she could identify: they were about the same age with similar backgrounds, one was behind the bar serving customers and the other sitting at it being served, and so on.

As my self-imposed publication deadline approached, I started having second thoughts; these morphed into a small panic when a man who bore a strange resemblance to the Islamic vigilante in Uzza, big and balding, came to say the Asr—the late afternoon prayer for Sunnis—beneath the branches of a large tree across the street from where I lived. This had never happened before.

He laid his prayer mat down facing east in the direction of Mecca and began the prostrations, kissing the ground and all that, reciting verses from the Koran which I could not hear from behind the double-pane bay window where I sat at a desk writing while watching the world go by.

All done, he picked up his mat—but rather than return the way he came, he crossed the street and slowly walked in the direction of my condo building, looking up (my apartment is on the second floor) and moving his head from side to side. If I had leaned across my desk and looked down, I could have told you the colour of his eyes. Like in horror movies, I was afraid to come face-to-face with my worst nightmare. When I finally did glance at the sidewalk beneath my window to the world, he was gone.

Had he returned the next day or the day after, I would have assumed he had simply found a place conducive to communing with Allah and left it that; however, he never returned.

I know that, should Uzza find an audience, violence will find me and my government will agree with the extremists that I had it coming. It is inevitable; it is a sign of the times. I would rather that, when the inevitable knocks on my door, it be after Uzza’s reputation has spread further than my neighbourhood and Riyadh, a regular visitor to boreal.ca where I posted excerpts of Uzza—including the chapter No Scarf, No Service where the vigilante makes an appearance with his stealthy burka-clad sidekick.

Riyadh is a regular. Undoubtedly, so are members of my city’s large Muslim community, which could explain the man’s resemblance to the character in Uzza. It should not have mattered, except that it fueled a reluctance to follow through on a promise made to a beautiful girl.

I started making excuses. I published Remembering Uzza: If Islam Was Explained to Me in a Pub in September. October came and went and I was running out of excuses. I know what you’re thinking: if the local ummah was already aware, why not give her the book and be done with it? You may be right. Maybe it was the sex, in the book that is.

Needless to say, no explanation of Islam would be complete without a discussion about Islam and sex, and Uzza’s character is not afraid to talk about it. Maybe it was these discussions that worried me. Little did I know. With that in mind, when I again showed up without the book, I said it was because I wanted her father, who was out the country, to read it first. He could order it from Amazon and have it delivered to wherever he was at the time, then decide if it was suitable reading material for his daughter. She looked at me as if I was from another planet.

The sunny warm summer and early fall of 2019 gave way to a contrarian November. One cold early November evening, I left her workplace thinking it was too busy for her to find the time to talk to me. I was more than a short distance out the door when I heard a voice calling, “Bernard, where are you going?” I turned around to find her next to me in attire totally unsuitable for the weather, asking if I wanted to come to back in and, I think, whether I had the book.

I hit upon another delaying tactic when we next met. I put fifty dollars and a letter containing an excerpt from my wife’s eulogy in an envelope. You could or could not deduce from the letter, about keeping an open mind and mutual respect and understanding, that my Lucette was dead. Her underwhelming curiosity about the life of an old man made it easy to avoid mentioning that I was recently widowed. It would probably have led to a display of emotions which could only have damaged a relationship that was evolving based on a mutual interest in Islam.

I gave her the envelope. She read the letter while I explained that, because she was busy with more important things, she might take the fifty (Uzza retails for $19.50CDN on Amazon.ca) and purchase a copy of my book when she had the time to read it. She kept the letter and handed back my fifty dollars. No more nonsense. She wanted the book, and she wanted it from me.

Needless to say, the next time we met I brought the book, and yes, another envelope, this one containing two hundred and fifty dollars and nothing else. I explained that I was purchasing her opinion for five hundred dollars; she would be in effect my consultant, and she would get the remainder when she reported back with her impressions of Remembering Uzza after having read the entire dialogue. If she accepted my conditions, her opinions about the book, for the time being, were for me alone.

She agreed, and I gave her the book. She promised to give it back. I said no, that it was hers to keep and I expected her to scribble all over it, and she would. She then hugged the book, beaming as if I had given her the Hope diamond. What a heartwarming sight that was. How could I not find her endearing?

As expected, the next time we met she had been too busy with her own life-changing priorities to read more than twenty pages, but she was okay with it—with Uzza, that is.

I had not seen her for more than a week when it happened. She had obviously been to the hairdresser or been with someone skilled in doing the impossible: improving on perfection. As she made her way to the stool next to me, the one nearest to the wall, she firmly stroked my back with the flat of her hand, from shoulder blade to shoulder blade; the type of greeting that you would expect from one who is more than a friend, or a very good one at the least.

I had forgotten what that felt like. For the last few years of Lucette’s existence even that commonplace, somewhat forceful gesture of affection was beyond her capabilities. A feeble bruised hand behind my neck was the best she could manage when I leaned over to kiss her goodnight.

In the four months or so since that serendipitous meeting on the patio on a street of patios, the only greeting we had exchanged was a light handshake, and now this. She sat down next to me and turned towards me, sometimes leaning against the wall or forward, sometimes sitting up straight. It didn’t matter; even when I looked into her eyes, I could not help but take in the exposed curvature of what the Prophet loved most in young women: their breasts. Maybe three buttons of her blouse were unbuttoned. Nothing unusual; we were not meeting in a convent and it was only how we found our-selves sitting next each other that offered my peripheral vision something truly inspiring.

It was as if the gods were conspiring to make this old man long for something that was very much a distant memory. And they were not finished.

She brought the book in anticipation of, I assume, a serious discussion. She placed it on the counter. She left it open—or maybe it was me who, perhaps inadvertently, after helping her find an endnote, left it open—at page 119, which was folded upon itself and acted as a bookmark.

Page 119 concludes the chapter No Paradise for Old Men, a prophetic title as it would turn out, where Uzza answers a question from Bob about whether “in Paradise they do it that way.” Page 119 also marks the end of a discussion about how holy warriors use rape, with virgins the preferred target, as a means of coercing innocent young girls into becoming suicide bombers. Nothing sexy about that either, but it didn’t matter.

That man beneath my window had me thinking conspiracies. If she wanted to spend a disappointing night in bed with a guy twice her age and then some, all she had to do was ask. What do they say about people who assume too much? That they make an “ass” of “u” and “me”, but mostly themselves.

Instead of continuing the discussion about what she had read so far, I started to talk about how I had spent much of the afternoon at Ottawa University arranging a memorial scholarship in my wife’s name. While I talked, she buttoned her blouse all the way to the top, and when I was finished, she said she had to go. As she got up to leave, she again stroked my shoulders, but this time in a more hurried way.

For someone who has lost a partner of more than thirty-eight years, the hardest thing to get used to is going to bed alone and waking up alone. Had I passed up an opportunity not to wake up alone? The thought was too much to bear. I had to find out.

The next time we met was a few days before Christmas. She greeted me in the same way she always had, except for that one time, with a smile and a “how are you” or something equally engaging. I think she was wearing that same little black dress as when we first met. It was the end of her shift. I asked if we could go someplace else, someplace more quiet. She got her coat and we walked to a nearby, nearly empty bar on the next block.

We sat down in a banquette across from each other. I wasted no time in asking her about what happened the last time we met. Her answer was both a relief and a disappointment. No, she had not tried to seduce me and she was sorry if I got that impression. But what about the book left open at that chapter? “You mean the one about anal sex; what about it?” Just like my Uzza, nothing fazed her.

Just like before, I changed the subject and started talking about me, only me. She seemed to be as attentive as if I was talking about Islam. I stopped myself. She had better and more fun things to do than listen to me talk about me. I knew her friends were waiting for her. This time I was the one who decided it was time to go. Before we left, I handed her a small box containing some of Lucette’s more whimsical jewelry: gold plated charm bracelets.

She opened the box and asked “Why?”

I explained that during one of, if not the most difficult times of my life, following my wife’s passing, her interest in my writing helped and I wanted to show my appreciation. To keep my emotions in check, I half-jokingly reminded her about what the Prophet said about people who wore gold jewelry in this world: that they would not be allowed to wear gold in Paradise. “That was for men only,” she said with a smile. I’ll have to look that up.

She told me that after Christmas she was going away for a few weeks, during which time she would be able to finish reading my book. Something I both looked forward to and dreaded; after that, what will we talk about? Will she still be interested in seeing me?

We walked to where I knew her friends were waiting. She stood there and I stood there, neither quite knowing what to do. What the hell, I gave her hug, then turned around and went home.

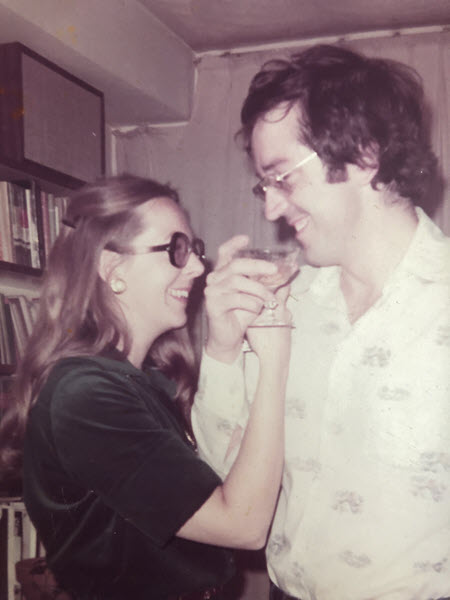

Except for an artistic rendering of my Lucette’s beautiful smiling face, which I hung at the end of the corridor leading to my bedroom and to which I say goodnight and good morning, I could not bring myself to put up any more pictures of her or us together. When I got home that night, however, I took out a framed photograph of the two of us in more carefree times and put it on my desk. It’s been there ever since.

As to my other beautiful girl, no matter what she said about that night when life again imitated art—when she made me feel that I was more than an acquaintance—I still think it was an Uzza moment. To understand what that means, you will have to read the book.

Part 2

The Green Bay Packers were playing the San Francisco 49ers in the NFC Championship game when I showed up at her place of work. I had not been there since our last get-together before Christmas. The place was wall-to-wall with fans watching the game on walls covered with TVs. The only seat to be had was at one end of the bar. If you were there to watch the game, the sight lines were not very good. It didn’t matter. I wasn’t there for that purpose, even though I am a fan of American football. They were drinking beer, eating their nachos, chicken wings and ribs; I ordered a salad and a glass of wine, settling in with my iPhone and the BBC.

I was poking at some lettuce with my fork when I looked up and saw her at the other end of the bar waiting on an order. She acknowledged my presence with what I thought was a tentative wave, but there was no mistaking that Mona Lisa smile. Maybe I should have let our last time together at that other place where mostly young people go to eat, talk and have fun be our last time together. Maybe I should leave.

All misgivings vanished when, maybe ten minutes later, she made her way to my end of the bar and told me how nice it was to see me again. She said she had finished reading the book, but tonight was obviously not a good night to talk about it, and to come back later in the week.

When I returned a few days later, she said to wait until her shift was over, when she got her coat and said she was ready to go. When we got outside, I suggested my place just a few blocks away. She gracefully declined. Perhaps I should have known better than to extend such an invitation, even if my intentions were realistic, except for a forlorn hope which springs eternal in old fools.

The place we ended up was where I went for brunch on Sundays. It was not the same atmosphere at all. We would definitely have been better off at my apartment and I would not again be left wondering, “What just happened?”

The lights were much too low, but at least it was reasonably quiet when we sat down at a banquette across from each other and started talking about the book. Towards the end of our discussion I handed over an envelope with the remaining $250 owed, saying that she had completed what I considered a contract to my satisfaction—in ways she will only understand if she reads this.

Our conversation about Uzza started innocently enough. She wished that—spoiler alert—the story had not ended so abruptly, that she could have gotten to know Uzza better. She praised my knowledge of Islam as superior to hers. I don’t know if that was a good thing. It was shortly after what I took for praise that she said that my portrayal of the Prophet hurt her deeply, that she was raised on believing Muhammad to be a good man, the perfect human being in fact, not the person in my book.

What she said reminded me of another young woman about her age, a little taller perhaps, with blond hair about the same length as my beautiful brunette’s, a vision of serene loveliness strolling in a long white chiffon dress, on what I believe was Les Champs-Élysées, next to a moving mass of grey shouting its murderous rage for the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo.

She attracted the attention of a journalist who caught up with her and asked what she was doing there. She stopped and looked at him as if he had asked the stupidest of questions. “Mais, ils ont insulté mon prophète!” (But, they have insulted my prophet!) she responded with visible indignation.

My beautiful girl may have attended primary and secondary schools in the Middle East but she did her undergraduate degree in Canada, and Islam was not part of the curriculum.

What she said about my honest portrayal of the historical Muhammad, which is based on what he said and did in authenticated hadiths, is probably the strongest argument I could make about letting religion have its way with kids. It is as if an Islamic education and upbringing can’t help but create the equivalent of the Manchurian Candidate with the trigger being anything bad said about Muhammad.

I am not saying that my beautiful girl’s reaction was the result of indoctrination equivalent to brainwashing, for I could not tell if what she said was in anger or sadness. I was trying to explain that my depiction of the Prophet Muhammad was not something I made up when whatever I was saying was drowned out by the disk jockey who had just set up his equipment. Speakers were now belting out the tunes at a decibel level to rival the noise made by jet engines on takeoff. I shouted to be heard by the man serving our drinks, that with only us and few people at the bar, maybe he could turn it down a bit? “No can do,” he said. The music was meant to be heard outside to draw people in from the street.

The noise level meant we had to hunch forward to be heard. Even then, because of the darkness, I could not tell by the look in her eyes how she really felt when she spoke those words.

There is a scene in Remembering Uzza where Gerry detects that Uzza is troubled by what they have discussed and reaches out to touch her hand. You guessed it; that is what I did after hearing my beautiful girl’s cris de coeur. Her hands were flat on the table. As I leaned forward to be heard, I could not resist doing what Gerry did for Uzza. The character Gerry was the right age to do something like that and not be misunderstood or look like a creep to an outside observer. If what she had said was in anger, I was adding insult to injury. When I took my hand off hers to take a sip of wine, both hands moved out of reach. I apologized.

It was getting late and the noise was making a meaningful conversation next to impossible. We decided to leave. When we got outside we went our separate ways, but not before I again hazarded a hug, which I think was reciprocated. Then again, it may be wishful thinking, not unlike what I am doing now while writing this book.